Reproducibility in science is of obvious importance, and the number of retractions and papers tackling this have highlighted the distance we still have to go. There's also been a lot of work on producing tools that make reproducibility easier, and a push to embed this through training. At the very least, the goals of the Recomputation Manifesto look to be closer now.

My thought here is about what is reproduced, not how. In particular, what is it that represents a computer simulation?

Papers versus images

To most academics, the currency is papers and grants. As no funding agency has yet required a reproducible grant proposal, a lot of focus has gone into reproducible papers. At the same time, there's been a lot of comment that "the academic paper is dead or dying", or at least won't be fit for purpose in the near future. There's a minor conflict here, which may be one reason why reproducible papers have gained less traction than reproducible code.

Leaving that aside, to me the paper doesn't represent the simulation. My simulations build on detailed thought, carefully constructed code, and the best analysis I can produce of the complex resulting data. With the same level of seriousness, your simulations are impressive work, but with weird voodoo magic I don't understand, and their simulations are just a fancy visualization package on top of a random number generator.

The serious point: to me, a simulation is

- the problem being studied;

- the questions we're trying to answer;

- how widely applicable, and accurate, we think our answers are.

Most of the detail that covers these points is summed up not in the paper, but in the figures and figure captions. The paper is "just" the framework and prose glue that holds the figures together.

A computer science analogy comes from Brooks' quote adapted for Object Oriented programming by Raymond:

Show me your code without your [classes] and I won't understand. Show me your classes without your code, and I won't need to see the code.

I believe the analogy holds for simulation papers and images. A simulation paper without images will either be unintelligible or far too long to read. A good set of images can show the ideas and key content behind the paper without needing the paper.

So, the image is the simulation. And this is a big problem.

The image as orphan

Hyperbole aside, images - unlike in-depth academic arguments - aren't confined to papers. Everywhere the work might be advertised - talks, websites, grant proposals and more - the image is doing much of the work: representing the simulation, standing in for the months of code wrangling and contentious analysis. That image that appeared on a student poster might, in a few years, be the key figure selling a grant proposal, or illustrating a research lab's work, or holding together a chapter of a thesis, or representing to another scientist all that is wrong (or right) about another field of research. How many problems result from people arguing about what they think a result means, thanks to arguing with the figure out of context, and the original context (code and analysis) can't easily be reproduced?

There is a link to be made with the amazing "artists' impressions" that NASA produces, often to illustrate new observational results. They're incredible feats that condense the state of the art science into easily grasped images. However, it's always clear that these aren't real. When the image is from a computer simulation, which is meant to be a cutting-edge model of how things "really" are, then it can have disproportionate impact on scientists and non-scientists when pulled out of context.

im2sim

One way to tackle this is to make the image really represent the simulation, by making it possible to replicate the full simulation (code, parameter files, data analysis scripts and all) just from the figure. Note that I'm using this definition of replicability versus reproducibility, even though I've loosely used reproducibility throughout this post. If the details are embedded in the figure metadata, in such a way that the simulation can be easily recovered, then it would be possible to link the figure with its original context in a reproducible way.

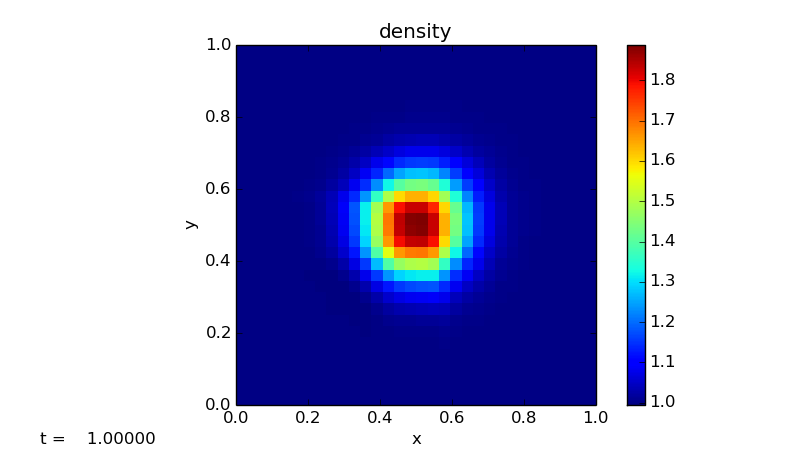

Here's an example, using the figure at the top of the page. To reproduce this figure, you'll need the im2sim code from this github repository, which is a simple python script, and the figure itself, which you can just "save as" directly from this page.

The idea I've used here is the simplest hack I could think of that would give the entire simulation. The metadata of the image contains the SHA1 hash of a docker container stored on dockerhub. This container includes the code to produce it (in this case, pyro2, which is Mike Zingale's code illustrating a number of CFD techniques) and a Makefile. im2sim reproduce will (assuming you have docker installed) pull the container, then tell you the command you need to run to reproduce the images, or the command to use to inspect the content of the container.

The alternative use of the script can be illustrated once you have the container associated with the image. im2sim mark can be called on the container. This will run the Makefile in the container, produce the images, and then edit the metadata of the images to include the SHA1 hash. Those images can then be distributed, and anyone can reproduce the simulation using just the image and the im2sim script.

Is this for everyone?

Let me rephrase that: should you download a script and image from the internet and run it on your machine, knowing that effective use of docker requires root permission on your machine? The answer is obviously, "No, you should not use this code!".

However, building something like this into your workflow would be a good idea. If you've already got a reproducible workflow then adding the metadata that gets back to the last analysis step producing the figures would be enough. Adding a link to, for example, a Jupyter notebook that produces the figure whilst explaining the analysis would be better. Any way that works!

Acknowledgements

The code to add the metadata to image files was taken from this code. It monkey-patches matplotlib to add the git hash of the local directory to the figure produced. This builds the reproducibility aspect into the workflow more naturally, and would be a better approach in many ways - it ensures the image automatically gets the metadata - but unlike the docker approach it doesn't contain the full workflow.

The setup of the docker container comes from this stackoverflow answer which references this Makefile. I've taken the approach but switched to python simplly to use one script for the lot.

Mike Zingale's pyro2 code covers a lot more than I've shown here. It's an excellent learning resource, especially used in conjunction with his detailed notes.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus